Meta Brown, Andrew Haughwout, Donghoon Lee, Joelle Scally, and Wilbert van der Klaauw

Meta Brown, Andrew Haughwout, Donghoon Lee, Joelle Scally, and Wilbert van der Klaauw

Second in a three-part series

Most of our about high levels of student loan delinquency and default has used static measures of payment status. But it is also instructive to consider the experience of borrowers over the lifetime of their student loans rather than at a point in time. In this second post in our three-part series on student loans, we use the Consumer Credit Panel (CCP), which is itself based on Equifax credit data, to create cohort default rates (CDRs) that are analogous to those produced by the Department of Education but go beyond their three-year window. We find that default rates continue to grow after three years and that performance by cohort worsened in the years leading up to the Great Recession.In order to create our cohort default rates, we must first assemble a history of default experiences at the borrower level. First, we identify the subsets of borrowers who are currently in default, which is defined as being 270 or more days past due. We then identify borrowers who have ever defaulted. As of the fourth quarter of 2014, 11 percent of all borrowers were in default, with an additional 7 percent of borrowers having defaulted in the past. Another 6 percent of borrowers were in earlier stages of delinquency, but not yet defaulted; fully 37 percent of borrowers had at least one missed payment on their credit report.

We next assign our borrowers to cohorts using loan origination information on the academic year in which the student stopped taking on new loans. This information allows us to assign each borrower to an “origination completion cohort” for each academic year. Our data do not provide information on graduation or dropout dates, but to the extent that student borrowers take out new loans in the last year of their education, this approach will be close to the concept of the school-leaving cohort of each student borrower. Note that our measures include federal PLUS and Perkins loans as well as private loans.

Cohort Default Rates—Nine Years Out

Cohort Default Rates—Nine Years Out

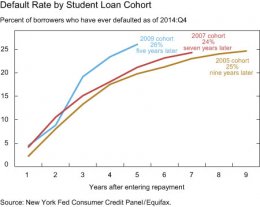

We can now produce default rates by this cohort breakdown. In our calculations, the denominator is the number of borrowers who entered repayment during a specific cohort year and the numerator is the number of borrowers from that cohort who have ever defaulted on their loan since they entered repayment. The chart below shows our calculations for the 2005, 2007, and 2009 cohorts. Roughly one quarter of each of the cohorts has defaulted as of the fourth quarter of 2014. Note that the default rate of the 2009 cohort has surpassed that of the earlier cohorts much more quickly. In fact, the chart shows a pronounced worsening of the cohort default rate schedules over time. CDRs at all durations are higher for more recent cohorts, with only one exception being the two-year default rate of the 2009 cohort. This exception should be interpreted with caution, however, as it was the sole data point affected by uneven credit reporting in 2011.

Keep in mind that we haven’t seen the full picture of 2009 borrowers who will default. Our calculations indicate a 19 percent three-year default rate for this 2009 cohort; but two years later, an additional 7 percent of borrowers have defaulted. The pattern for earlier cohorts strongly suggests that this rate will continue to rise. Our 2005 cohort had a three-year default rate of 13 percent—but this is only half of the defaults that we see nine years out.

Who is defaulting?

CCP data show that early delinquencies are worse among lower-balance borrowers, and that’s true for default rates, too. The results for the 2009 cohort, presented in the chart below, are striking: the highest default rates, at nearly 34 percent, are among the borrowers who owe less than $5, 000. These borrowers made up 21 percent of the 2009 cohort. The default rate among the borrowers who leave school with more than $100, 000 in debt is almost 50 percent lower, at 18 percent.

Conclusion

Our analysis of borrower distress uncovers some new facts. Perhaps most important, cohort default rates appear to have been worsening over time, and the two- and three-year analyses that feed much of the public discussion are only part of the story. CDRs continue to rise in years four through nine. Second, defaults appear to be concentrated among the lowest-balance borrowers, who may not have completed their schooling, or may have earned credentials with lower payoffs than a four-year college degree. Finally, snapshots of delinquency and default rates miss the fact that many borrowers who are current today have had serious stress in the past. Only about 63 percent of borrowers appear to have avoided delinquency and default altogether.

In our next post, we’ll discuss how quickly these borrowers have been paying down their balances. We will find that many borrowers who have avoided defaulting are still struggling to pay off their debts.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Meta Brown is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Andrew Haughwout is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Donghoon Lee is a research officer in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Joelle Scally is the administrator of the Center for Microeconomic Data in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Interesting facts

Additional information

|

Loan Calculator Mobile Application (Tim O's Studios)

|